This post first appeared on the Democratic Audit blog in April 2017, and then on the Political Studies Association Parliaments Group blog in May 2017.

Elections are a central and necessary feature of any democratic system. However, elections are also highly disruptive events. The process of government is effectively halted to allow for a period of campaigning. Laws are wrapped up quickly or abandoned altogether. Ministerial are diverted into party business and major announcements from government departments and a wide range of other public bodies are postponed. This is even more the case if an election is called unexpectedly. Even in states which do not have a fixed period between elections, the existence of a recognised electoral cycle lends predictability to the system and means that elections are less disruptive. There is a further lag following an election. If a sitting government is re-elected, some policies and appointments are likely to be carried over and the policy process may be restarted fairly quickly, if a government changes then a more substantive and lengthy reboot is usually necessary.

If elections are disruptive to the process of government, they are even more disruptive to the scrutiny process. In the UK, a new government is usually formed fairly quickly in the days following a general election. In contrast losing opposition parties often go through a period of upheaval, particularly if party leaders are challenged or resign. In parliament, new governments usually enjoy a honeymoon period as new MPs find their feet, and may be reluctant to challenge the new government’s electoral mandate. The reformulation of parliamentary scrutiny bodies also often takes somewhat longer than the establishment of a new government. The process of creating select committees can only begin once it is known which MPs have been offered Ministerial positions and are therefore excluded from consideration. Moreover, the process of electing select committee members and Chairs takes time and now means that it will be several weeks before a full complement of select committees are in place.

One committee whose work has been significantly disrupted by the Prime Minister’s decision to seek a general election in June is the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (ISC). The ISC is not a parliamentary select committee but is a cross-party committee of MPs and Peers whose role is to oversee the work of the intelligence and security agencies. The committee was reformed in 2013 to become a committee of parliament with enhanced powers and a more expansive mandate. However, the committee has been worryingly quiescent in recent years and particularly since the 2015 general election. It is not clear whether this is the result of changes within the committee itself and the adoption of a new mode of operating or a more general marginalisation of the committee on the part of the government. Nevertheless, the announcement of a general election is an unwelcome interruption to the ISC’s work, further delaying the publication of reports, interrupting ongoing inquiries and leading to an inevitable change in the membership.

Delayed reports

Perhaps the most immediate impact on the ISC of an early general election, is to further delay publication of the committee’s report on the UK’s involvement in lethal drone strikes in Syria. Following the 2015 general election the committee announced that one of its immediate priorities was to conduct an inquiry into ‘the intelligence basis surrounding recent drone strikes in which British nationals were killed.’ The inquiry followed an announcement by the Prime Minister in September 2015 that three UK nationals had been killed in targeted drone strikes in Syria. On 16th December 2016, the ISC announced that its report on lethal drone strikes had been passed to the Prime Minister and that following a process of review and redaction it expected the report to be published ‘in the New Year.’ More than four months later the report is yet to appear, and it is unlikely now be published until after the general election.

Some delay in the publication of ISC reports is not uncommon. Although the ISC is a parliamentary committee, because of the nature of its work, its reports are first submitted to the Prime Minister and subject to the redaction of sensitive material, before being laid before parliament and published. Although this is a necessary precaution, it also means that the timing of the publication of ISC reports is in the hands of the government. This is not the first time that the delay in publishing ISC reports has been a cause for concern, nor is it the first time that a general election has interfered with the process. The committee has periodically complained about the delay between submission and publication of its reports. Moreover, prior to the 2010 general election the ISC completed a report on the draft guidance given to intelligence officers involved in the interrogation of detainees. Although the committee clearly expected the report to be published at that time, the government held up publication. Following the election the in-coming committee announced that the previous committee’s report would not now be published, but that the government’s guidance would be published instead. It is to be hoped that this does not set a precedent.

Ongoing inquiries

The general election will also, of course, interrupt the committee’s ongoing work. The ISC’s most pressing current concern is the much delayed inquiry into the role of UK intelligence agencies in the treatment and rendition of detainees. The establishment of a judge-led independent inquiry into the treatment of detainees by British personnel since 9/11, was announced by the Prime Minister, David Cameron, in July 2010. It would, the Prime Minister hoped ‘report within a year’; an inquiry which was costly and open-ended, he added, ‘would serve neither the interests of justice nor national security.’ In December 2013, following the publication of an interim report the inquiry ceased its work, on the grounds that ongoing legal action against the British government on the part of several detainees would prevent it from completing its work in the near future. Responsibility for the inquiry was passed to the ISC who were provided with extra resources in order to take it on. In its most recent annual report, published in July 2016, the ISC reported that the detainee inquiry was now the committee’s ‘main focus’ but that ‘it is a detailed and long-term Inquiry into an important issue and is expected to occupy the Committee for some time.’ This will be the second general election in the four years since the ISC took over the inquiry, and it seems unlikely to hasten its completion.

The ISC also has a statutory obligation to publish an annual report on its work. This is usually published in June or July, shortly before parliament goes into its the summer recess. The timing of the annual report has been affected by previous general elections, but publication has usually been brought forward to enable an outgoing committee to complete its report before an election. A snap general election means that this has not been possible this time. Moreover, the timing of the election coupled with the time it will likely take to appoint a new committee after the election (see below), means that it is unlikely that the latest annual report will be published before the autumn. While ISC members often claim that it is one of the hardest working committees in parliament, judged on the basis of its output alone it is not the most productive of committees. The current committee has published just two reports since the 2015 general election.

Changing membership

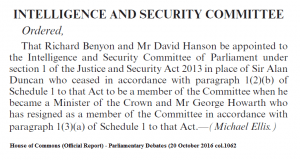

As with all parliamentary committees the membership of a new ISC will need to be selected following the general election. The ISC is reconstituted following each general election usually with a combination of new and existing members. Under arrangements introduced in 2013 the members are now appointed by parliament from a list nominated by the Prime Minister in consultation with opposition leaders. The Chair of the committee is then appointed by its members from those selected to serve on the committee.

There will be some inevitable turnover in membership of the ISC which raises a number of concerns. Two members of the current committee, the Labour MPs, Fiona Mactaggart and Gisela Stuart, have announced that they are standing down at the election and will not therefore be available to serve. Mactaggart and Stuart are also the only women on the committee. Although membership of the ISC has historically been dominated by men, the presence of women on the committee has had a substantive impact. The committee has been chaired by two women, and in 2015 Hazel Blears was instrumental in prompting the committee to examine the role of women in the intelligence community. Despite this women have been notably under-represented on this committee. The opportunity to establish a gender balance on this committee would be a welcome development, but if the polls are correct, the pool of Labour women to replace Mactaggart and Stuart may well be small.

Turnover of membership will also undermine the experience of the committee. Mactaggart is the longest serving MP on the committee, although she has only been on the committee since January 2014. In terms of members with past experience on the committee, the current ISC is the least experienced since the ISC was first established in 1994. The committee appointed after the general election will be more inexperienced still. This matters because intelligence is an area in which few parliamentarians have a great deal of background knowledge or experience and members of the committee often attest to a steep learning curve while serving on it. The departure of a number of long-serving members during the last parliament served to erode the institutional memory of the committee and this is a resource which is not easily restored. It is to be hoped, at least, that the services of the current Chair, Dominic Grieve, are retained following the election. Although Grieve was new to the role, his experience as Attorney General and his reputation for independence meant that his appointment was widely welcomed. He has not been in place long enough yet to demonstrate whether that faith was justified.

Perhaps more worrying is the possibility that there will be a significant delay in appointing a new committee. There is, once again, an unfortunate precedent in this respect. Following the 2015 general election a new ISC was not put into place until September, some four months after the election. It is not clear why the process took so long in 2015, but ISC members were not selected until all Ministerial appointments had been made and all select committees had been established. It may also be delayed if opposition leaders resign and the nomination of new members does not take place until a new leader is in place. The delay in appointing a new committee does little to dispel the impression that ISC membership is a compensation for a loss of Ministerial office. It would be unfortunate if it also became viewed as a second-tier parliamentary committee. Moreover, the prolonged absence of the principal mechanism for providing democratic accountability for Britain’s intelligence and security agencies is not conducive to good governance or national security.

The Intelligence and Security Committee is just one committee of parliament. The disruptive impact of a snap general election will be felt across many others. There are, however, some worrying precedents which suggest that the impact on the ISC may be particularly acute. The formation and work of the current committee have been characterised by delay, it would be reassuring if this was not carried over into the next parliament.