This post presents the results of a survey of the representation of women on legislative intelligence oversight committees in forty countries. It is not a comprehensive survey but does represent a broad cross-section of states and of legislative intelligence oversight committees. A significant proportion of these states (25) are located in Europe, but the survey also includes oversight committees from national legislatures in North and South America, Africa, Asia, Australia and New Zealand.

There is considerable variation in the form, powers and mandate of these committees. Some are typical standing committees operating under the rules of procedure of their respective legislatures while others, such as the new Canadian National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians, are special committees of parliamentarians appointed by the executive and with powers which are not enjoyed by other legislative committees. The members of most of these committees are drawn from national legislatures, although three, from the Netherlands, Norway and Portugal, are external bodies which scrutinise the work of the intelligence and security agencies on behalf of their national parliaments. Thirteen are joint committees comprising members from both chambers in a bicameral system, while twenty-five are drawn from a single chamber either from a unicameral or bicameral system. The US is the only bicameral legislature included here in which both legislative chambers have their own intelligence oversight committee. Most are dedicated intelligence oversight committees with a mandate focused on the scrutiny of the intelligence and security agencies in their respective states, although for some the scrutiny of intelligence is part of a broader mandate focused on other policy areas such as defence or internal affairs. While there is considerable variation, one of the striking facts illustrated by this survey is that some form of accountability of intelligence agencies to elected legislative bodies is now the norm in many democratic, and some non-democratic, states.

In most cases details of committee membership was collected from the websites of the national parliaments to which the committees report or the websites of the committees themselves. The availability of this material is also testament to the extent to which legislative scrutiny of intelligence has become a standard feature of the work of national legislatures. In most cases the data is, as far as can be determined, up to date. Some countries have yet to establish new committees following recent elections, most notably Argentina and the UK. In the case of the UK, the data reflects the membership prior to the 2019 general election, while details of the membership of the Argentine joint committee is limited to the seven Senators who have thus far been appointed. Figures for the proportion of women serving on each committee was compared with the proportion of women in the chamber or chambers from which each committee was drawn using data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) Parline database.

The presence of women on legislative intelligence oversight committees

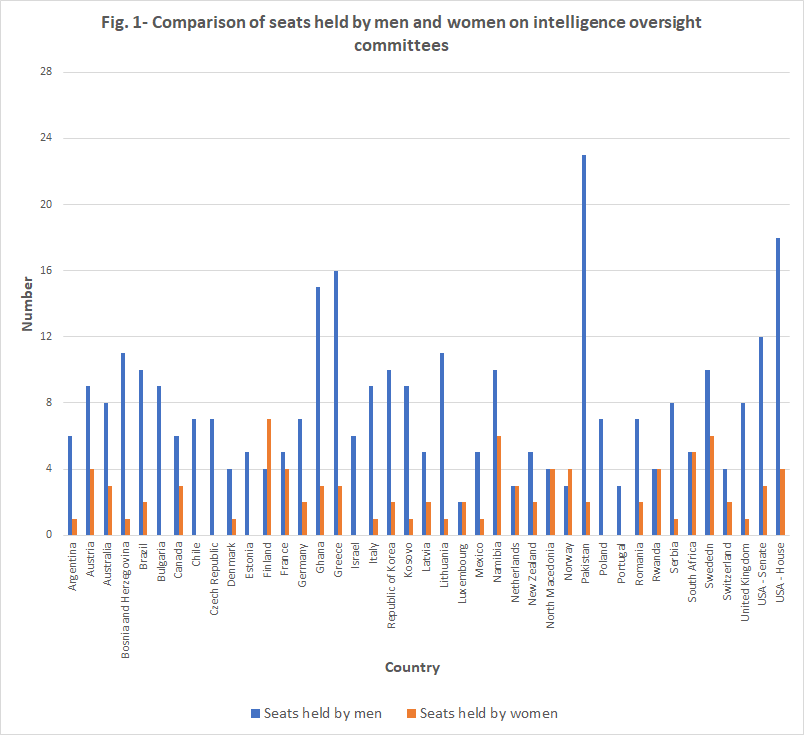

The data from this survey indicate that in many states women are significantly under-represented on legislative intelligence oversight committees (fig.1). In only two states, Finland and Norway, do women hold more seats than men on the legislative intelligence oversight committee, while in four states the number of seats on the committee are shared equally between men and women (Luxembourg, Netherlands, North Macedonia, Rwanda and South Africa). In all the remaining committees in this survey, women are not just outnumbered by men, but the number of seats held by men is more than double the number of seats held by women. Seven states have no women at all sitting on their intelligence oversight committee (Bulgaria, Chile, Czech Republic, Estonia, Israel, Poland and Portugal), while nine committees have only one woman member (Argentina, Bosnia Herzegovina, Denmark, Italy, Kosovo, Lithuania, Mexico, Serbia and the UK).

Moreover, it is not simply the case that the absence of women from legislative intelligence oversight committees reflects a broader problem with the representation of women in national legislatures. In most cases the proportion of women sitting on a legislative intelligence oversight committee compares unfavourably to the proportion of women sitting in the legislatures from which these committees are drawn (fig.2). In only one state, Canada, is the proportion of women on the committee on a par with the proportion of women in the legislature as whole. In ten states the proportion of women serving on an intelligence oversight committee exceeds the proportion of women in the legislature as a whole (Brazil, Finland, France, Ghana, Luxembourg, Netherlands, North Macedonia, Norway, Romania, South Africa). However, in the remaining twenty-nine states included in this survey, women comprise a smaller proportion of the membership of their state’s legislative intelligence oversight committee than the chambers from which these committees are drawn. In some cases, the disparity is quite marked. Mexico, for example, is fifth in the IPU’s ranking of the percentage of women in Parliament, with women comprising 48% of members of Parliament, but only one of the six seats on its intelligence oversight committee is held by a woman. Women comprise more than 30% of parliamentarians in Denmark (40%), Serbia (38%), Italy (35%), Kosovo (33%) and the UK (30%), but in all of these states the proportion of seats held by women on their intelligence oversight committee is around 20 percentage points lower, with women holding only one seat on each committee.

Moreover, it is not simply the case that the absence of women from legislative intelligence oversight committees reflects a broader problem with the representation of women in national legislatures. In most cases the proportion of women sitting on a legislative intelligence oversight committee compares unfavourably to the proportion of women sitting in the legislatures from which these committees are drawn (fig.2). In only one state, Canada, is the proportion of women on the committee on a par with the proportion of women in the legislature as whole. In ten states the proportion of women serving on an intelligence oversight committee exceeds the proportion of women in the legislature as a whole (Brazil, Finland, France, Ghana, Luxembourg, Netherlands, North Macedonia, Norway, Romania, South Africa). However, in the remaining twenty-nine states included in this survey, women comprise a smaller proportion of the membership of their state’s legislative intelligence oversight committee than the chambers from which these committees are drawn. In some cases, the disparity is quite marked. Mexico, for example, is fifth in the IPU’s ranking of the percentage of women in Parliament, with women comprising 48% of members of Parliament, but only one of the six seats on its intelligence oversight committee is held by a woman. Women comprise more than 30% of parliamentarians in Denmark (40%), Serbia (38%), Italy (35%), Kosovo (33%) and the UK (30%), but in all of these states the proportion of seats held by women on their intelligence oversight committee is around 20 percentage points lower, with women holding only one seat on each committee.

Committee Leadership

Even more striking than the predominance of men on legislative intelligence oversight committees is the fact that the chairs of these committees are almost exclusively held by men. Only one of the forty-one oversight committees in this survey is currently chaired by a woman, the Intelligence and Security Committee of New Zealand. This is not, however, the result of a positive decision to appoint a woman to chair the committee. Rather it stems from the fact that legislation requires that the New Zealand Intelligence and Security Committee be chaired by the Prime Minister. A post which is, of course, currently held by a woman, Jacinda Ardern. The arrangements for membership of the New Zealand committee are not ideal in terms of ensuring the committee’s independence from the executive, but if this practice was adopted in other states there would be significantly more women chairing intelligence oversight committees. Indeed, on the basis of the evidence presented here, it is tempting to conclude that that it is easier for a woman to be elected to the highest office of state than to become chair of a legislative intelligence oversight committee.

The situation is slightly better on committees which provide for some kind of deputy chair. Of the twenty-six committees in this survey which have a named vice or deputy chair, seven of these positions are held by women (Finland, Kosovo, Latvia, Namibia, Norway, Rwanda and Switzerland). It is noticeable that some of these committees (Finland, Norway, Rwanda) also have a gender balance in terms of membership. However, in the case of Latvia and Switzerland, the position of deputy chair is held by one of only two women members of the committee, while the deputy chair of the oversight committee of the Kosovo intelligence agency is the only woman serving on the committee.

Why are women under-represented on intelligence oversight committees?

It is not clear why these committees are dominated by men. As noted above, in most cases the proportion of women on these committees is not directly corelated to the presence of women in the chambers from which they are drawn. Another supply-side explanation for the tendency to appoint men to these committees may relate to the proportion of women who are perceived to have sufficient seniority or experience in this area. There is a tendency in many states for the members of intelligence oversight committees to be senior politicians, including those with experience of ministerial office. If women are less likely to be appointed to senior positions in government, this may impact on the likelihood that they will later be considered for a position on an intelligence oversight committee.

While many women may be excluded from such committees on the basis of seniority, research on the appointment of women to parliamentary committees more generally has also found that appointments are often gendered, with women more likely to be appointed to committees focused on stereotypical women’s issues such as education and healthcare. In the current UK Parliament, for example, there is only one woman member of the foreign affairs select committee and two women members of the defence select committee, while women hold five out of eleven seats on the health and social care committee and four out of eleven seats on the education select committee. This may reflect some element of issue preference on the part of women MPs, although this may in turn reflect the fact that women put themselves forward for membership of those committees to which they are most likely to be appointed. Moreover, for security reasons intelligence oversight committees are often smaller than other legislative committees and demand for places may be high. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that in some cases women are pushed aside by sharp-elbowed men keen to play on their masculine credentials as defenders of the state.

Does it matter?

The arguments for fairer representation of women in legislatures have been well rehearsed. While many states are some way from achieving gender parity in their national legislatures, it is now widely accepted that the composition of representative bodies should reflect the society they serve. Moreover, arguments have also moved on beyond the need to provide for fairer representation of different groups to focus on the benefits that those with different experiences might bring to the scrutiny functions of legislatures.

There is some evidence that the presence of women on intelligence oversight bodies has had an impact on their work. Diversity in legislative intelligence oversight committees may be important not only from a democratic perspective but also because such bodies may well be drivers for diversity within intelligence agencies themselves. In the UK, for example, the Intelligence and Security Committee has conducted two inquiries into diversity and inclusion within the UK intelligence community. Ongoing monitoring of diversity in recruitment and employment practices is now a standard part of the work of the committee. This focus was initiated and taken forward by the, admittedly few, women who have served on the committee. Similar work has now also been undertaken by the Canadian parliamentary intelligence oversight committee. Intelligence agencies are not representative bodies but ensuring that a wide range of views and experiences are considered as part of the intelligence process may go some way towards enhancing intelligence analysis and improving the intelligence product.

Making questions of diversity and inclusion a feature of the scrutiny role of legislative intelligence oversight committees is just one, obvious, example of the impact women may have on the work of such committees. Ensuring that intelligence oversight is not dominated by homogenous groups of men with similar backgrounds and experiences may enhance their capacity to hold governments and intelligence agencies to account in a myriad of other ways.

The following post on the role of women on the UK Intelligence and Security Committee was posted for International Women’s Day in 2015: “Jobs for the boys? Women members of the Intelligence and Security Committee.”