The Investigatory Powers Tribunal will today consider the legality of a convention whereby the communications of parliamentarians may not be subject to interception by the intelligence agencies. In a case brought by the Green MP, Caroline Lucas, the Peer, Jenny Jones, and the former MP, George Galloway, the tribunal will test the strength and legality of the so-called Wilson doctrine.

The Investigatory Powers Tribunal will today consider the legality of a convention whereby the communications of parliamentarians may not be subject to interception by the intelligence agencies. In a case brought by the Green MP, Caroline Lucas, the Peer, Jenny Jones, and the former MP, George Galloway, the tribunal will test the strength and legality of the so-called Wilson doctrine.

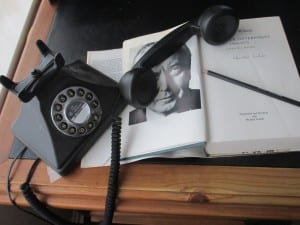

The Wilson doctrine is a convention established by the then Prime Minister, Harold Wilson in 1966, when in response to a series of questions in the House of Commons, Wilson informed the House of Commons that ‘there is no tapping of the telephones of honourable Members, nor has there been since this Government came into office.’ He went on:

I reviewed the practice when we came to office and decided on balance—and the arguments were very fine—that the balance should be tipped the other way and that I should give this instruction that there was to be no tapping of the telephones of Members of Parliament. That was our decision and that is our policy. But if there was any development of a kind which required a change in the general policy, I would, at such moment as seemed compatible with the security of the country, on my own initiative make a statement in the House about it. I am aware of all the considerations which I had to take into account and I felt that it was right to lay down the policy of no tapping of the telephones of Members of Parliament.

Five days later, in response to a question in the House of Lords, the Lord Privy Seal added that this policy also applied to members of the House of Lords.

Successive Prime Ministers have all expressed their continued commitment to the Wilson Doctrine. Moreover, it is apparent that the scope of the convention has expanded in recent years. Developments in communications technology have prompted a series of parliamentary questions about the scope of the doctrine. In 1997, Tony Blair stated that the Wilson doctrine also applied to electronic communications, and then in 2002, perhaps exasperated by continued questions on the subject, stated that that ‘the policy refers to all forms of warranted interception of communications’.

The principle which underpins the Wilson doctrine is that MPs’ communications should be treated differently to those of ordinary members of the public. It is based in part on the notion of parliamentary privilege which protects MPs and Peers from prosecution for anything they might say as part of the proceedings of Parliament or any of its committees, and also allows each House the freedom to regulate its own affairs. However, it is not clear to what extent this encompasses all communications entered into by members of Parliament, and also how this relates to subsequent legislation on the operation of the intelligence agencies, which makes no mention of the Wilson doctrine. In the tribunal’s considerations much may hang on its understanding of what constitutes parliamentary proceedings. However, as the Wilson doctrine has no basis in law it may also decide that it is something on which is it not prepared to pass judgement.

Prior to Wilson’s statement the assumption was that the communications of parliamentarians were not treated any differently to those of other members of the public. In 1957 a committee of inquiry into the interception of communications concluded that:

So far as we can determine, a Member of Parliament is in exactly the same position as any private citizen in regard to the interception of his communications unless those communications were held to be connected with a proceeding in Parliament.

The committee struggled to define what might be constitute communications connected to a proceeding in Parliament, but assumed a rather limited approach providing the example of a telephone call relating to an intended parliamentary question. In 2005 the Blair government considered rescinding the Wilson doctrine on the grounds that with legislation in place to authorise and oversee the interception of communications it was no longer necessary to rely on such a convention. Blair was supported in this by the Interception of Communications Commissioner who argued that the Wilson doctrine flew in the face of the constitution by assuming that MPs’ should be treated differently to other citizens. However, in the face of considerable disquiet in Parliament, including within his own Cabinet, Blair dropped the idea.

There is a widespread assumption that the doctrine provides for a blanket ban on intercepting the communications of parliamentarians. There are however, a number of important caveats to the Wilson doctrine and it is quite clear that MPs’ communications have been intercepted since Wilson made his statement. Firstly, Wilson’s statement does not preclude the interception of parliamentary communications it simply states that if interception takes place Parliament would be informed at some point. This highlights a fundamental contradiction at the heart of the Wilson doctrine, which is that whilst it is designed to protect the communications of Members of Parliament, it may at any point be in abeyance, with it simply being the case that parliament has not yet been informed. Indeed, the carefully worded statements of successive Prime Ministers’ in relation to the Wilson Doctrine do not indicate that the communications of parliamentarians are not being intercepted, but merely that if they are, it is with the Prime Minister’s approval and Parliament has not yet been made aware. Former Ministers interviewed for our research argued that the Wilson doctrine merely set a higher bar for the authorisation of interception which means that warrants to intercept the communications of parliamentarians will be subject to much closer scrutiny than other warrants, and are likely to authorised by the Prime Minister.

Moreover, it is far from clear that the interception of communications in particular cases would involve a setting aside of the Wilson doctrine requiring parliament to be informed at all. It could be argued that the general policy remains that the communications of parliamentarians will not be intercepted while in particular cases, and with the correct authorisation, they may be. In the same way that in general the communications of members of the public will not be intercepted, but that in specific cases and with the correct authorisation, they may be. This does, of course, raise the question of whether the Wilson doctrine provides any protection not afforded to ordinary members of the public. What may make a difference in the current case, particularly in the light of recent revelations about the collection of communications data, is if it can be shown that parliamentarians’ communications have been intercepted as part of a general trawling of communications data. Although this, of course, may be hard to prove.

While the Wilson doctrine may have expanded to encompass new communications there are also a number of other limitations to its application. It is a privilege which does not apply to members of other legislative assemblies such as the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Assembly or the Northern Ireland Assembly. Moreover, it only applies to interception by the intelligence agencies. Since Wilson made his statement there has been a significant expansion in the use of interception by other agencies, most notably the police. When meetings between the Labour MP, Sadiq Khan, and a constituent in Woodhill Prison were covertly monitored in 2006, this was not considered a breach of the Wilson doctrine on the grounds that the interception was instigated and carried out by the police rather than the intelligence and security agencies, and had not therefore been subject to Ministerial authorisation.

All of which raises the question of whether the Wilson doctrine has any real meaning at all. The practice as set out by Wilson allowed for it to be set aside at any time, and only required the Prime Minister to reveal this to Parliament at some point. The communications of some parliamentarians have certainly been intercepted at various points since 1966. The monitoring of the communications of Sinn Fein Members of Parliament in the 1990s is an open secret, but are not the only examples. However, while it is quite possible that the Wilson Doctrine has been routinely set aside in a number of particular cases for some time, and that successive Prime Ministers have not felt able to reveal this to Parliament, this would arguably be in keeping with Wilson’s commitment, and would not contradict the assurances of successive Prime Ministers that the doctrine remains in force. At the same time, a significant growth in the number of government agencies now able to carry out surveillance, and particularly the expansion of covert surveillance by the police, means that the Wilson Doctrine provides only partial protection to the communications of parliamentarians and may, either by accident on design, be circumvented. Finally, questions remain about whether parliamentarians should be treated differently to other members of the public in this respect, and if so whether this should be extended to members of other legislative chambers. If this is to be the case then legislation would provide greater protection than a caveat-laden convention enunciated on the floor of the House of Commons.

This post draws on the article ‘Tapping the telephones of Members of Parliament: the ‘Wilson doctrine’ and Parliamentary Privilege’ by Andrew Defty, Hugh Bochel and Jane Kirkpatrick which was published in the journal, Intelligence and National Security, vol. 29, no. 5 (October 2014), pp.675-697. The article contains much more on the background and operation of the Wilson doctrine, including analysis of cases involving Sinn Fein MPs and the Labour MP, Sadiq Khan. We also submitted evidence in relation to the Wilson doctrine to the government’s 2012 consultation on parliamentary privilege.